Greenberg DIR Noah Baumbach; SCR Jennifer Jason Leigh, Noah Baumbach; PROD Jennifer Jason Leigh, Scott Rudin, Lila Yacoub. US, 2010, color, 105 minutes.

Greenberg DIR Noah Baumbach; SCR Jennifer Jason Leigh, Noah Baumbach; PROD Jennifer Jason Leigh, Scott Rudin, Lila Yacoub. US, 2010, color, 105 minutes.

Noah Baumbach is emerging as one of American cinema’s finest directors with each of his films containing increasingly sophisticated, acute observations of human personalities and behavior that are more subtle and yet more intense. While Baumbach’s contemporary and occasional collaborator, Wes Anderson, has struggled to pop out of his bubble of fetishistic style and increasingly formulaic profundity to progress and mature towards a deeper and richer level of cinema, Baumbach keeps maturing, keeps transcending. Baumbach’s Greenberg [2010] is a masterfully subtle narrative that is born primarily from character, from the inner worlds of its characters. Greenberg contains a disarming simplicity, but beneath this are layers of complexity, depth, and quiet, brutal honesty that is capable of slowly broad siding your psyche.

By some, Greenberg is considered the commercial manifestation of the Mumblecore movement, a relatively obscure cinematic sub-genre, which is also known as Bedhead Cinema, Slackavettes, and several other monikers that denote the Generation X of its day. Unlike that sub-genre, however, Greenberg is not truly a lo-fi, organic slice-of-life. Greenberg may have a kinship with Mumblecore films thematically (if Greenberg is indeed considered within the Mumblecore movement), but it differs from the Mumblecore films most notably in its filming technique. The film’s cinematographer, Harris Savides, says that the film’s natural look has more in common with the new European style and very little in common with Mumblecore’s visual aesthetic which, according to Savides, is “really, really, really lo-fi.”[1] The cinematography, visual metaphor, and dialogue in Greenberg stand in stark contrast to the supposed Mumblecore minimalist adherence to extreme lo-fi and improvisation. (Actually, some say that there is no cohesive aesthetic style at all within the Mumblecore movement; rather, Mumblecore film’s are tied together through the exploration of similar themes.[2])

While the visual aesthetic of Greenberg might look lo-fi, it was very carefully designed. Greenberg’s visual aesthetic certainly exudes a naturalism; the film’s brilliant cinematographer, Savides, who has specialized in a ‘70s look for a number of recent films set in the ‘70s (Zodiac [2007], American Gangster [2007], and Milk [2008]) employed a number of techniques such as use of a softer film stock, natural lighting, and hand-held filming to achieve the distinct visual look of Greenberg.¹ Savides cinematography intently expresses and magnifies the melancholy of the character’s life, which is one of the reasons why the film harkens back to the look and feel of ‘70s cinema—it was during the melancholy of the ‘70s when a whole generation saw their ideals from the ‘60s peter out and amount to relatively nothing, and all the seekers were set adrift, desperately searching for something meaningful to latch onto. In many ways, the spiritual derailment of the ’70s parallels Greenberg’s existential condition but rather than a shift in eras, his condition is propelled by a shift in age.

In addition to the film’s cinematography and images, the film’s dialogue seems organic, but it is not. In an April 2010 interview on Charlie Rose, Ben Stiller discussed how Baumbach directed him to speak every line in the script as it was written; there was little-to-no improvisation. Rather than this being regarded a fascist ego trip, one should regard this as necessary because almost every line of dialogue is a manifestation and revelation of inner character and the characters’ relationships with one another. There is so much subtle, revelatory meaning to be found in the images and dialogue that don’t register upon first viewing. Given the film’s rather mundane L.A. suburban setting, some might dismiss Greenberg as a slightly run-of-the-mill, low-key indie with superb cinematography. It’s only in subsequent viewings that the film’s literary complexities through images and dialogue begin to emerge.

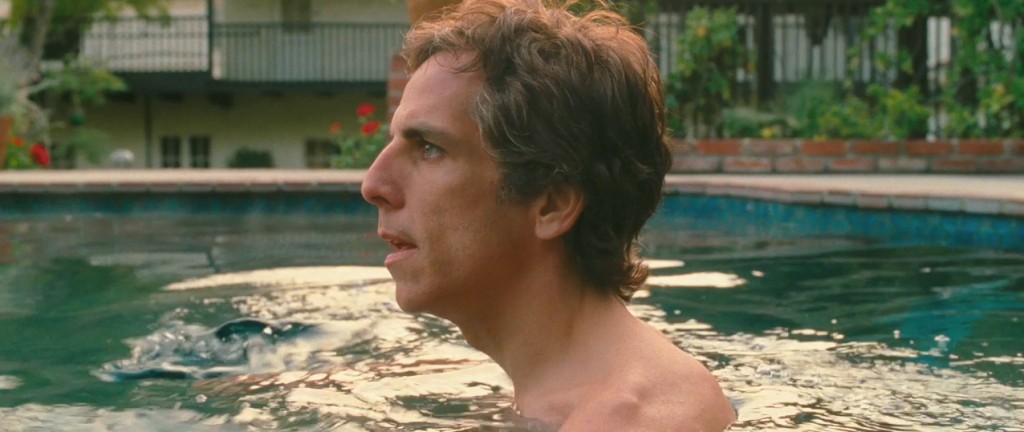

The images in Greenberg are not random but are chock full of metaphor and symbolism. Greenberg swims, or rather struggles, to dog paddle across his brother’s pool, a metaphor for the difficulty he has in navigating his life. A dead animal floats in the pool at a teenage coke-fueled party—a symbol of Greenberg’s present condition and a symbol of how the younger, crueler generation views someone like him. The flailing balloon figure reveals Greenberg as a man flailing around in his own life mired in a maze of psychological and emotional difficulties. The visual metaphors and symbolism in Greenberg work because Baumbach so seamlessly weaves them into the fabric of the film’s narrative to the point that they are a natural part of the story; they don’t stand out as metaphors and symbolism until later critical reflection.

And even when there are no sophisticated metaphors revealing the nature of Greenberg, there are situations and encounters that continue to reveal Greenberg’s inner character such as when Greenberg at the teenage party acts like a teenager himself while coked out, self-indulgently playing his favorite music and addressing the teenagers at the party with a bizarre familiarity normally reserved for close friends. There is a letter writing campaign that allows Greenberg to channel his almost bottomless anger, which seems reveals his lack of self-esteem and hatred of himself, the source of which may be rooted in the contentious relationship with his brother (possibly a thematic furtherance of the brothers-father dynamic in Baumbach’s The Squid & the Whale [2005]). Greenberg’s social awkwardness is astutely revealed as he struggles with insecurity and self-doubt while preparing food at his self-proclaimed lame outdoor pool party and feeling self-conscious about it all even though it’s for people that he hardly even knows.

Greenberg’s partial teenage existence is revealed in such small moments that they could be easily missed: asking his friend Ivan not to sit on the speaker and it sounding as if they are two kids at his parents’ home, randomly cutting his hair out of boredom like a teenager might do, calling two girls during his birthday dinner at Frank & Musso’s especially when the “lesser” girl gives him that added boost of self-esteem to call the “better” girl, whimsically choosing to go to Australia at a moment’s notice, and viciously holding onto ideals that really are an outlet to channel his misdirected anger. And if that weren’t enough, Baumbach shows Greenberg surrounded by children at a child’s birthday party looking completely disconnected in what could be perceived as a dual layer of metaphor: Greenberg is adrift and immature compared to his friends at the party who have progressed with their lives and started families, but it could also be viewed as glimpse into what Greenberg might have been like as a child—just as disconnected in childhood as in adulthood. Greenberg’s teenage immaturity even manifests itself in the film’s ending when the 40-year-old Greenberg ultimately relates his deepest feelings to Florence (Greta Gerwig) over the phone on a voicemail (an ending, by the way, that is brilliant not only in its ability to find yet another way to manifest the inner character of Greenberg but in its ability to find a creatively unconventional way to end the film).[3] Finally relating his deepest feelings about Florence on her voicemail is not only a perfect representation of Greenberg’s inner character but is a perfect representation of the youth culture’s increasing inability to communicate—to express sincerity—except through technology.

Low self-esteem, guilt, and regret are the heart of Greenberg. While we initially experience Greenberg redirecting this toxic stew of self-loathing onto the world with his humorous stream of letter writing, the narrative eventually forces Greenberg to face this toxicity or lose Florence with whom he is falling in love. This inner toxicity causes Greenberg to repel Florence with such abusiveness at times that it is truly hard to watch, yet the brutal authenticity of it is mesmerizing. The film hints at the source of this toxicity, which quite possibly is his mother, whose funeral he did not attend. This particular thematic focus seems an extension of Baumbach’s exploration of a deep mother and son conflict that he explored in The Squid & the Whale.

Much has been made of Stiller’s performance in Greenberg in terms of depth and dramatic intensity and how he has finally stretched himself as an actor, but people seem to forget that Stiller has acted with similar depth and intensity before especially in 1998 in what could be considered the year of Stiller’s flirtation with something other than cartoonish comedy, so Greenberg should really not be considered Stiller’s Punch-Drunk Love [2002]. In that year, Stiller appeared in Neil Labute’s satire on yuppie narcissistic emptiness and sexual envy, Your Friends & Neighbors [1998], which was as equally character driven as Greenberg and as satisfying to watch, not to mention squirm inducing given its brutal honesty about the moral corrosiveness of young urbanites. Stiller also appeared that year in Permanent Midnight [1998] in what was a somewhat radical departure for Stiller playing the true life drug-addicted television writer Jerry Stahl. (Interestingly, a corrosive mother/son dynamic also figured prominently in that film.) Even though the general intensity of that film was unfortunately muddled by a visual design that didn’t evoke the film’s emotional content, Stiller inhabited the character.

Greenberg possesses various sprinkles of irony: a kind of anti-hipster hipsterism at times and a direct commentary on Greenberg’s obsessions with irony at others—a sort of meta irony. Greenberg wears a Steve Winwood “Back in the High Life Again” concert t-shirt, which seems like a self-indulgent form of anti-hipster hipsterism while Greenberg’s “you have to get past the kitsch” commentary about the song “It Always Rains in California” could be classified as an honest attempt to comment on irony. But Greenberg only flirts with what has become a somewhat tiresome characteristic of independent filmmaking (and our culture in general)—the increasing obsession with ironic commentary over sincerity. Because cinema—at least cinema verite—is a reflection of our society—indeed our human condition—the tiresome hyper presence of ironic commentary in contemporary film is a reflection of the heavy ironic commentary in our culture, which itself may be caused by the heavy ironic commentary of film—a never-ending feedback loop with each loop more ironic than the previous loop. Ironic commentary can be a useful tool, but it can easily slide into an elitist, condescending attitude that eventually becomes obnoxious. In general, ironic commentary indicates a distance between you and a cultural object and can be necessary when something is unworthy of sincerity and appreciation, but if that tool is overused, it blooms into cultural and social snobbery.

Why are hipsters such a derided subculture? It’s not because they like indie, or alternative, culture (or more appropriately for these times, mainstream culture from an ironic standpoint). It’s because they constantly ridicule culture, both mainstream and alternative, to the point that they barely have a sincere affinity for anything. Everything they hate and even everything they “like” becomes a situation of ironic commentary. They sincerely like very little in culture, but even that is not the core reason why they are so derided. They sincerely like very little in culture except that which is “pure,” which is really saying anything that is fashionable at the moment, a shallow attitude that ultimately is revealed as a symptom of their deeply buried sense of cultural elitism. Films, especially comedies, used to rely on rich snobs as stock characters for derision and villainy. Hipsters are the modern day equivalent.

Stiller’s Reality Bites [1994] deftly touched upon that very issue of hipster elitism of the Beatnik-coffee-house-poet variety (even though one could argue that the film cops out in the end). Baumbach’s Kicking and Screaming [1995] didn’t focus on the cultural elitism of constant irony, but did focus on characters struggling with the debilitating, paralyzing effects of constant hyper analysis and pop-culture references. In a way, Greenberg is a joint capstone to Stiller’s and Baumbach’s focus on Generation X that began in the mid-90s with Reality Bites and Kicking and Screaming. The character of Greenberg is what eventually happened to some of the characters from those two films, but in a way, Greenberg comes full circle in an attempt to move beyond that state of kitsch and irony and the residual disdain of the world so as to immerse himself in something unpretentious, something real. When Greenberg so carefully hangs the child’s picture on the wall at the end, he is not only displaying a selfless caring for another human being, he is also finally facing the lost, pained boy inside him and giving him a second chance.

Justin Baker

End Notes

[1] David Schwartz, “That ’70s Look: The Throwback Naturalism of Cinematographer Harris Savides,” Moving Image Source, March 26, 2010, http://www.movingimagesource.us/articles/that-70s-look-20100326

[2] Dennis Lim, “A Generation Finds Its Mumble,” The New York Times, August 19, 2007, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/19/movies/19lim.html?_r=2&8dpc

[3] The link between the Mumblecore sub-genre and Greenberg is furthered by the presence of Gerwig who has acted in a number of films by Mumblecore director Joe Swanberg including LOL [2006], Hannah Takes the Stairs [2007], and Nights and Weekends [2008]; Gerwig co-wrote Hannah Takes the Stairs with Swanberg et. al. and Nights and Weekends with Swanberg, and she co-directed Nights and Weekends with Swanberg.