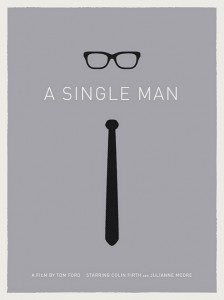

George Falconer (Colin Firth) is a homosexual man living in 1962 Los Angeles who has lost the love of his life in an accident. In this aftermath, George trudges through each day struggling to hang on to a sense of meaning while he copes. He focuses on exquisitely managing the everyday details of his existence not only because he is an educated English gentleman but because it is a distraction from his tragedy. At the outset of A Single Man [2009], which is based on a 1962 novel by Christopher Isherwood, it is clear that George exists in a rigid, controlled environment of routine with a meaning that has begun to slowly decay leaving him to contemplate suicide. Intertwined with this tragedy, George copes with the stigma of being homosexual in the early ‘60s when homosexuality was still the love that dared not speak its name—at least in the social and academic stratospheres in which George moves. One condition directly affects the other: George has never been able to publicly acknowledge his relationship with his partner, and, therefore, is not able to publicly grieve after his partner dies. The film’s one sheet, which pictures black framed eye glasses and a black tie without a human being, is supposed to be a metaphor for George having to keep his homosexuality and his grieving invisible. Despite the original intentions of this metaphorical image, the one sheet’s image of a tie and glasses minus the human being inadvertently becomes the metaphor for A Single Man’s obsession with aesthetics over thematic clarity, narrative logic, and authentic emotions.

The director of A Single Man, Tom Ford, is primarily a fashion designer who instilled the Gucci label with world class reknown and went on to become an icon in the fashion world. From an outsider’s vantage point, most fashion designers appear to have a complexity only in terms of their craft as clothing designers; from my perspective, many of them seem rather superficial, but Ford bucks that stereotype. Ford is an aesthete: he ponders and theorizes about the nature of beauty. He is both an intellectual and a romantic, which informs his theories on what is beautiful and subsequently informs his creations as a fashion designer. He is a renaissance man: before becoming a fashion designer, Ford studied architecture at the Parsons School of Design. He eventually lost interest in architecture, but it is this intellectual interest in the world outside of fashion that helped him to excel as a fashion designer. Ford’s designs are embedded within large and deep contexts. His intellectual attitude towards fashion emerged from an attitude that style isn’t just for style’s sake; the style of his clothing designs became manifestations of his philosophical, historical, social, and cultural perspectives and expressions.

In addition to intellectual perspectives and expressions, Ford’s clothing designs are also the manifestation of a romantic perspective. He has deep appreciations for flawless skin tones and sensual sexuality. He seems to especially have a penchant for the days of the late ‘70s when popular conceptions of sexuality emphasized softness and naturality—when silky clothes erotically clinged to braless female bodies with natural curves. He laments the cold, heartless, aggressive, butcher-shop sexuality of contemporary culture. Ford’s romanticism runs the full spectrum from inspirational to existential. In a December 2009 interview with the Los Angeles Times, Ford described how “everything in life is bittersweet for me, because when I see something beautiful, I also see it aging, old, dead, gone.”

Ford’s intellectual-romantic push-pull is the classic dialogue between function over form and form over function, and Ford’s success as a fashion designer seems to be directly related to his astute ability to emphasize and balance the two. As his career progressed, Ford began to express himself through fashion ads that were provocative not simply for their sexual content but for being rooted in social and cultural commentary that turned its critical eye occasionally onto the fashion world itself. To add to his already impressive creative achievements, Ford has now directed a film. Ford’s dual condition of romanticism and intellectualism has allowed Ford to successfully transition from fashion to film because a good film has a captivating aesthetic layer of imagery that captures a viewer’s attention while ultimately propeling the viewer into the film’s deeper emotional and intellectual thematic layers, which are rooted in large and deep contexts—a parallel model that can be found to a particular degree in Ford’s fashion design technique.

Ford is certainly a purveyor of beauty. A Single Man could be described as impeccably tasteful and beautiful on par with a well-groomed and glossy fashion ad. George lives in a beautiful mid-century modern home that has a subdued, organic, masculine color palette of browns and grays, which is an interesting contrast to the colorful, almost Populuxe hues of Mad Men and any number of films and television shows set during the mid-century modern period. And while I wonder if the color palette of his home is even authentic to that time period (it seems more like a retro version of the ‘60s rather than an authentic version), it does successfully reveal George’s character, which is reserved and introverted. George’s clothes are also impeccable and blend perfectly with his exquisitely decorated home; all of his clothes appear to have the same subdued, monotone color palette.

In addition to directing the film, Ford designed George’s wardrobe. He did this not just because Ford is a fashion designer but because George’s wardrobe is a significant expression of his character. Ford put so much thought into George’s wardrobe that he even created a back story for the suit that George wears throughout the film: Ford posits that George, having come from a wealthy English family, would have visited his family in England every few years and would have taken the opportunity to get a tailored suit from Saville Row during such a visit. The suit that George wears over the course of the one day in 1962 in which the film takes place (although in my opinion it’s not readily apparent that the film takes place over the course of one day) would have been tailored in 1957 on George’s last visit home. Ford even went to Kubrickian lengths of detail to sew a tailor label inside the suit jacket with George’s name and the date when the suit was created. All of this detail is fetishized in a series of scenes towards the beginning of the film as we see George dressing for work and moving about his home.

Ford also carefully designed both the home décor and wardrobe for George’s best friend, Charley (Julianne Moore). Despite being close friends, Charley’s aesthetic differs sharply from George’s. So does her personality. She could be described as the shallow, narcassistic, alcoholic cousin of Norma Desmond. Charley exists in much colorful, gaudier, diva-like surroundings when compared to George’s conservative, organic palette. In developing her character, Ford conjectured that Charley would have known the top artists and designers in Los Angeles and would have been way ahead of the curve for 1962—before pop art had saturated pop culture across the board. In a December 2009 interview with Fresh Air, Ford elaborated on the image of Charley applying her make up in the mirror with one side of her face full of false eyelashses and the other side without: he wanted to visually communicate a slowly decaying beauty who was no longer relevant to the corners of society that value physical beauty over other things. While Ford succeeds at creating an indelible image, he unfortunately seems to be so in love with the general aesthetic of Charley’s life that the exqusite imagery smothers any significant notion of her slow decay. The same can be said for Ford’s vision of George. The muted color palette and obsessive attention to aesthetic detail actually works incredibly well at first in terms of character, but the film becomes mired in it and never progresses beyond it except for a rather lame attempt at the ending for profundity that mirrors the main character in American Beauty [1999], yet another film with a relatively cold, elegant aesthetic that explored the similar theme of the stigma of homosexuality amidst the existential malaise of suburban America. It is at this point that it becomes clear that the films aesthetic fetishism is not just a character study but the point of the film itself. A Single Man would have worked if it examined the character’s obsession with the aesthetics of his life as a way to avoid anything else, but it doesn’t do this either.

For his first foray into film directing, Ford seems to have been heavily inspired by films and televisions shows such as Far from Heaven [2002], Mad Men [2007], and to a particular extent Revolutionary Road [2008] especially when considering the presence of Julianne Moore and the cover-your-ears-and-you’ll-miss it auditory cameo by Jon Hamm. Like those productions, A Single Man deals with the repressed, fascist social morality and existential malaise amid America’s post-war, increasingly hyper-consumerist mid-century modern period. It seems inevitable that Moore would be in this film; she has cornered the market on playing iconically unsatisfied women in mid-century modern period films (Far from Heaven, The Hours [2002], The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio [2005], and now this). (As a side note, even though the television show Pushing Daisies [2007] does not at all deal with mid-century modern, A Single Man contains a cameo from the lead of that show, Lee Pace; I suspect that Ford, being the aesthete he is and Daisies having an aesthetic quality of the highest pedigree, felt inspired to give Pace a cameo.) But, in terms of aesthetics, A Single Man seems to really be Ford’s answer to Mad Men. While it is coincidence, it’s amusing that the title, A Single Man, is the singular of Mad Men, which is especially true when considering the thematic weight of the two.

Both A Single Man and Mad Men have the same fetish for period detail and take place at the same time (early ‘60s) during the Cuban Missile Crisis and on the cusp of the huge political, social, and cultural shifts in the United States of the mid to late ‘60s. It has been noted that Mad Men’s creator, Matthew Weiner, is so obsessed with his show being period perfect that he is faithful to décor, fashion, and everything else down to the month that any given episode takes place; if an episode takes place during June of 1962 nothing in the production design can be dated after June of 1962, and yet interestingly Weiner is also aware of that everything in the real world is not always at the cutting edge. Weiner ensures that some of his characters, especially the less afluent characters, on the show are wearing dated clothing, wearing dated hair styles, and living with dated furniture, which is the way it is in reality. (The British director Alan Parker also noted this in his production design for Angel Heart [1987]; Angel Heart takes place in 1955, but a lot of elements in the production design are a mixed bag of period pieces from years prior to 1955.) The degree to which the period detail is fetishized in Mad Men is probably matched only by Todd Haynes in Far from Heaven or by Wes Anderson in…take your pick. The only difference is that the fetishized period detail in Far from Heaven and Mad Men doesn’t overtake the themes and emotional content of their stories the way it does in A Single Man.

Period detail was fetishized to a particular degree in Far from Heaven because Haynes was trying to replicate not only a time period but, more so, the look of a film from a particular time period. Haynes wanted the film to appear as if it had actually been filmed in the 1950s; he painstakingly replicated the lighting techniques of that time, solicited a period-perfect score from Elmer Bernstein, and even employed extras that did not look like real small-town people but people who looked like backlot actors—the kinds of actors that would have been used in most Hollywood films and television shows from the ‘50s when authenticity was not the rule and artificiality was. It has been widely noted that Far from Heaven was Haynes’ attempt to create a Douglas Sirk film; in fact, Far from Heaven has been described by one critic as the greatest Douglas Sirk film that he never made. But the fetishistic attention to detail in Heaven is not primarily to serve the geek pleasures of film aesthetes but to be able to create the kind of Sirk film that Sirk was not able to make in terms of thematic depth and frankness. It is in this that Far from Heaven’s fetishistic attention to detail serves a greater purpose and not for its own pleasure. And with Mad Men, the thematic material has almost never overwhelmed its thematic explorations. While Weiner may fetishize the period detail (and it’s hard not to do so given the sumptuous styles of the time including the Florence Knoll Bassett décor of the show’s corporate offices and the sexy layered undergarments), the complexity of character and story, all of which are couched in historical, political, social, and cultural contexts, never suffers; it’s not relegated to a secondary consideration. Unfortunately, the same can’t be said for Ford’s A Single Man.

Beyond the aesthetics, A Single Man certainly explores similar thematic territories as Far from Heaven and Mad Men, Revolutionary Road, and to a particular extent, even American Beauty. Far from Heaven, Mad Men, and a A Single Man explore the taboo of homosexuality amid mid-century social mores. Mad Men, Revolutionary Road, and A Single Man all deal with the emerging existential malaise amidst the mid-century modern period. And while American Beauty does not share the mid-century modern thematic strand as the other films do, it too focuses on repressed homosexuality and the existential malaise that comes from living in suburbia and a hyper-consumerist culture. A Single Man is set during the Cuban Missile Crisis just as Mad Men is in season two, but the Cuban Missile Crisis doesn’t seem significant thematically in A Single Man at least the way it is portrayed in the film version; I suspect that it may have been woven into the novel in a more thematically significant way assuming that it was present. (I haven’t read the book.) Whereas in Mad Men, the international crisis is given a particular degree of dramatic significance in relation to its characters, in A Single Man, the crisis is inexplicably introduced and then thrown away as if a minor point; the inclusion of the crisis has the feeling of melodrama—a lazy way to interject some quick dramatic weight into the story.

This is a good example of how Ford is lacking in the thematic realm as a director. Throughout the film there is a solid presence of thematic weightiness, but it always remains heavily submerged; even something that’s supposed to be weighty such as George’s attempted suicide seems presented in a strangely cavalier, off-hand manner. In the December 2009 interview with Fresh Air, Ford said that George was doing a dry run of his suicide that he was to perform later, but it’s not exactly clear that this is the case when watching the film; in fact, that lack of clarity is characteristic of the handling of most of the film’s thematic material: there is a relative thematic transparency that is missing. In addition to a lack of thematic clarity throughout the film, there is also a slight pretentiousness in particular parts of the film especially the conclusion. The film’s ending seems to completely undercut the preceding narrative; if George was going to reunite with his love in some kind of metaphysical afterworld then what was the point of showing his dramatic struggle unless the struggle somehow allowed him to join his love in the afterworld. If this is the case within the film’s reality, then the logic is not apparent, which relates back to the film’s thematic clarity. The film’s ending seems an imitation of the profound ending in American Beauty in which the main character discovers the true meaning of life right before he perishes.

A Single Man is not without its signficant themes and thematic moments. There is one scene in the film that stands out as having depth and weight. George addresses his university students in class and addresses the general concept of fear and its specific manifestations: “…the fear of being attacked. The fear that there are communists lurking around every corner. The fear that some little Carribean country [ed. note: Cuba] that doesn’t believe in our way life poses a threat to us! The fear that black culture may take over the world!” The unspoken fear that he is alluding to is the fear of homosexuality amid the increasingly whitebread, homogenized culture of the United States at that time. The scene is also subtlely addressing the need for homosexuals to remain invisible in the society of that day. The scene is handled with deft in a rare moment that is relatively stripped of obsession with visual aesthetics. If only A Single Man contained more thematically weighty moments such as these and subdued its obsession with aesthetics. It is ironic that one of the film’s primary themes is homosexuals having to remain invisible in an intolerant world when in fact the thematic significance in most scenes is what is invisible amidst the dedication to its aesthetics. Any significant thematic moments (the classroom speech about fear and being invisible, the phone call about George’s partner’s death, George and his partner sharing a quiet moment reading together) drown in impeccable attention to style and detail. The majority of the film buries its thematic material under mounds of glittery yet seemingly unsubstantial imagery, and sometimes the relatively empty imagery is all that exists. A Single Man is like a sliver of hearty cake smothered in mounds of excessively sugary frosting. Despite the film’s thematic clarity and periodic pretentiousness, one must acknowledge that Ford has still done a remarkably well in his freshman effort especially when considering that filmmaking is not his primary creative pursuit.

The fact that A Single Man has obvious cinematic influences is not a problem. Many great films are influenced by other great films. The problem lies in the fact that A Single Man pales in comparison alongside most of the other productions. If not for A Single Man, Revolutionary Road would be the weakest in this collection of films about the mid-century modern period. Revolutionary Road had the misfortune to come out after Mad Men had started it is long, storied rise to recognition, and in comparison, Road seemed shallow to Mad Men. Both Road and Mad Men deal with similar themes of existential despair except that Road’s perspective doesn’t seem authentic, or at the very least, mature. Road’s perspective of its couple’s suburban predicament seems ridiculous and immature; the film’s overwrought perspective of the central couple succombing to an existential death simply by living in the suburbs seems more like a problem with the characters’ maturity levels than it does with the cultural shortcomings of suburban living. Road would be a much better film if it had only tweaked its perspective and recognized how childish its main characters’ immature romanticism is rather than validating it. And it is with great irony that Mendes directed the similar American Beauty, which was also an examination of the meaning of life in the quiet dread of suburban life, because that film ultimately championed the idea that life’s beauty was found in the little things amidst the “cultural death” and “relationship wasteland” of the suburbs which Denis Leary so eloquently addressed in No Cure for Cancer: “Happiness comes in small doses folks. It’s a cigarette , or a chocolate chip cookie, or a five second orgasm. That’s it, okay?! You cum, you eat the cookie, you smoke the butt, you go to sleep, you get up in the morning and go to fucking work!” The most satisfying of this canon is Mad Men. Far from Heaven is certainly a great film and one of the best of the the 2000 decade, but it is great more in terms of its cinematic trickery, which makes you think you are actually watching a film made in the late 50s, than for its exploration of bi-racial love and homosexual longings. Far from Heaven’s characters and story are indeed poignant, but because of the intentional melodramatic tone and intentional hyperrealistic style, the poignancy doesn’t have quite the same emotional impact as Mad Men, which is strives for a more authentic drama and strives to be somewhat less conscious of its art direction. In terms of substantive depth, Ford is not shallow person. His fashion design seems to spring forth from complex and deep perspectives on society and culture. It’s just that in the world of film Ford hasn’t yet learned how to clearly communicate the thematic perspectives that are so clearly beneath his veneer.

Ultimately, what hampers A Single Man and zaps the film’s emotional weight as much as its layer of aesthetic fetishism and its layer of thematic muddiness is its layer of hyperrealism. The film’s hyperrealism is embedded within its retro style, its period iconography, and it’s logic, and it largely elevates the film’s world out of a significant degree of authenticity. As for period iconography, the film is stocked with supporting characters that are archetypes of that time: the neighborhood boy playing cowboys and indians, the meek yet sweet housewife quietly accepting her position in a patriarchal marriage, sailors on leave hanging out a bar, greasers, and mod girls smoking cigarettes with looks of cool, empty disdain. These aren’t real people but, rather, types of people. Adding the retro style to these iconographs propels these supporting characters into an even more heightened world of hyperrealism. And then there is the hyperreality of the film’s logic, which falters primarily in its (contradictory) presentation of homosexuality as it would have existed in the world at that time. The world that Ford presents is a world that inexplicably exists within two parallel universes in which homosexuality must remain completely invisible yet is instantly recognizable in the most casual of encounters. It seems to contain two modes in which homosexuality is hidden unless you are homosexual, in which case you can immediately tell without question those others who are homosexual. Perhaps I just don’t understand the nature of homosexuality enough, but I found multiple such encounters throughout the film almost absurd: George’s student has nothing but certainty that George is homosexual despite the fact that George gives almost no indication that he is homosexual. And then there is George running into a homosexual greaser in front of the liquor store—the confident recognition that both are homosexual is almost instantaneous, and it occurs in public. And all of this is ironic given the film’s theme of the invisibility of homosexuality in the early ‘60s. A Single Man almost plays out like a homosexual fantasy layered with retro iconography in which homosexuality is invisible to everyone except the homosexual characters themselves. It’s quite ironic that this film is supposed to be about the forced invisibility of homosexuality even though it has its main character bumping into one homosexual supporting character after another with each encounter instantly resulting in the almost aggressive awareness that both characters are homosexual.It is ironic that A Single Man subtley condemns society’s perception of homosexuality based on artificially constructed perceptions all the while delivering this message through artificially constructed aesthetics and artificially constructed emotions, so while America may have skewed perceptions about homosexuals and their lifestyles, this film seems to also have skewed perceptions of homosexuals and their lifestyles. It wants to have its cake (buried beneath mounds of aesthetic frosting) and eat it too.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with the use of hyperrealism in a film, but its use depends on the context of the film. Far from Heaven employs an intentional hyperrealism to illicit the affect of watching a movie that had been filmed in the ‘50s. David Lynch began Blue Velvet [1986] with hyperrealistic images of small-town life including red flowers against the backdrop of a white picket fence and an impossibly blue sky with fluffy clouds as a counterpoint to the subsequent images of a more “realistic” primal and even sadistic human nature; although, one could successfully argue that Frank Booth’s world of S&M was just as a hyperrealistic as the presentation of the sunnier side of small-town life. Even if one successfully argued that Lynch never transcends the initial hyperrealistic images of Blue Velvet into something real, at least Blue Velvet transcends the aesthetic fetishism that Lynch obviously has for the film’s objects and iconography towards a thematic perspective about the moral and immoral nature of human beings whereas Ford becomes mired in it in A Single Man. (Whether Lynch’s thematic perspective transcends a hyperrealism is another story; one could argue that Lynch’s vision of the world in Blue Velvet remains mired in a hyperrealism throughout, which results in an overly simplistic and unrealistic vision of the dichotomy of human morality.)

Unfortunately, A Single Man isn’t about undermining its hyperrealistic presentation of the world that George lives in, a strategy that would have been valid. The film’s color palette does shift from a muted palette to warmer hues as George begins to feel something other than melancholy and begins to realize that there just might be something or someone to live for after all, which is an attempt to inject some kind of emotional authenticity into the film, but ultimately, the film revels in its hyperrealism, and it is in this that keeps A Single Man from transcending into something authentic and emotionally moving. Ford doesn’t seem to have been able to fully extricate himself from the extreme hyperrealism of fashion advertisements that were so wonderfully parodied in the Saturday Night Live commercial for Compulsion. Ford’s inability to fully extricate himself from the hyperrealism of the fashion advertising world in A Single Man is ironic given that many mid-century period films have a thematic foundation that explores the existential malaise brought on by the hyperconsumerism that emerged in post-war America as a result of the hyperrealism expressed in American advertising of that period. Even though A Single Man doesn’t directly link the character’s existenial malaise of having to keep his homosexuality invisible to the corporately homogenized culture promoted by Madison Avenue, it is in there. Mad Men certainly deals more directly with this thematic material primarily because it is about Madison Avenue. Regardless of the context, A Single Man portrays something that feelslike an inauthentic homosexual existence in the 1960’s whereas Mad Men’s portryal of Salvatore struggle seems a little more authentic. (Far from Heaven’s seedy back alley bar and absurd homosexual rendevouzs can be forgiven given that the film is intentionally hyperrealistic.) Ford is at least up front about the fact that the reality portrayed in the film strays from gritty authenticity. In the December 2009 interview with the Los Angeles Times, Ford described his aesthetic as “enhanced reality.”

The only cinematic nourishment to get from A Single Man aside from a few significant moments sprinkled throughout the film are the film’s images. If one can mentally strip away the negative connotations of the aesthetic fetishism and hyperrealism embedded in the images, some of images are indelible. The film begins with a hauntingly beautiful slow-motion image of a man submerged in water struggling to reach the surface. There is an otherworldy image of a girl in a bright blue dress holding a scorpion. There is the cool, slightly sinister image of George driving by a nuclear family on their lawn pointing his finger at them as if to acknowledge them but perhaps “shooting” at them and their irritatingly fascist homogeneity. There is a striking image of Janet Leigh’s eyes in an extremely large advertisement from Pscyho [1960], which George parks his beautiful vintage Mercedes in front of. And among all of these intriguing images, Ford has woven in a beautiful soundtrack of haunting retro Hitchcockian-thriller melodies, which is reminiscient of Hayne’s use of a score by Bernard Hermman for Far from Heaven to elicit that instant retro feel.

The powerful nature of these and other images in A Single Man is hard to ignore. A Single Man’s mise en scene is undeniably captivating in the same way a physically beautiful person who is well groomed and well poised is captivating at first glance. But when one begins to dissect beneath the skin of the beautiful object to study its real complexity is when the deeper value or lack thereof comes to light. It’s when one considers the striking images in relation to the obssesive aesthetic fetish, the thematic muddiness, and the overwhelming hyperrealism, that the images begin to seem empty. The significance of these images seem to amount to nothing more than the slick images employed in advertisments, which is ironic given that Ford seems to have an obvious obsession with Mad Men, a program that thematically is about peeling back the layers of the Madison Avenue assault on the psyches of the American public and revealing the underlying manipulation of advertisement—what someone once called the biggest psychological experiment ever perpetrated on the American public.

Images straddle the line between aesthetic and thematic. Images exist to capture the viewer’s attention, but they also exist to communicate a perspective; truly successful cinematic images are striking because they simultaneously achieve both functions.Some viewers though only require the cinematic images they crave and digest to be strikingly beautiful and some viewers only require their cinematic images to be thematically substantive. And therein lies what will probably spark the eternal debate between the lovers of this film and the detractors of this film; between those that only require their cinematic images to viscerally stimulate them and those that require their cinematic images to have thematic perspective. From my perspective, A Single Man is Tom Ford’s fashionable existential fantasy played out on screen and his cinematic objet d’ art. What should have been a feature-length film with the sheen of a exquisitely produced fashion commercial is a fashion commercial at the length of a feature-length film. A Single Man feels like a two-hour commercial for Calvin Klein in the same way that Anthony Minghella’s aesthetically pleasing The English Patient feels like a two-hour commercial for Banana Republic.

Justin Baker