Paul Hackett (Griffin Dunne) is an ordinary, middle-class man with deeper longings lurking right below the surface–he reads Henry Miller, and the hidden desperation of his character is hinted at through the film’s subtle references to intellectual aspirations and of unknown artists being discovered. One evening, Paul Hackett meets a girl (Rosanna Arquette) who seems to be the antidote to his increasingly coma-like existence, but he doesn’t know that she is going to lead him right down the rabbit hole. After Hours [1985] is a bold, bizarre slip into a comically nightmarish world from which Paul can not escape.

Paul Hackett (Griffin Dunne) is an ordinary, middle-class man with deeper longings lurking right below the surface–he reads Henry Miller, and the hidden desperation of his character is hinted at through the film’s subtle references to intellectual aspirations and of unknown artists being discovered. One evening, Paul Hackett meets a girl (Rosanna Arquette) who seems to be the antidote to his increasingly coma-like existence, but he doesn’t know that she is going to lead him right down the rabbit hole. After Hours [1985] is a bold, bizarre slip into a comically nightmarish world from which Paul can not escape.

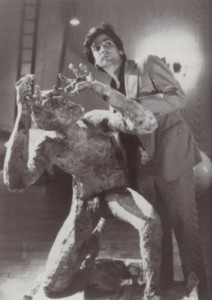

After Hours is steeped in Existentialism including allusions to Franz Kafka (apparently, the dialogue between Paul Hackett and the bouncer at Club Berlin is lifted almost word-for-word from a story by Kafka titled Before the Law). Through an increasing complex chain of logic, Paul becomes more and more trapped especially by the women he encounters all of whom seem to represent the same woman: all are blond, all have similar hair styles, and all are very eccentric; it’s only their ages that keep increasing incremently. The film never explains the reason that these representations of the same woman are tormenting Paul, and rightfully so; this non-explanation is in keeping with Kafka’s The Trial and Existentialism in general: the universe is a cruel, uncaring place, and amidst a particular degree of logic, there is no over-arching apparent reason to most of what occurs; some things are just beyond our capacity for understanding and will always remain a mystery. In addition to direct references to Existentialism, the symbol of Paul’s emotional plight is a sculpture that closely resembles Edvard Munch’s The Scream, which to me is closely associated with the sense that existence is a banal horror. So it is a perfect unfolding of the story when Paul becomes trapped–literally–in his own Scream-like sculpture towards the end. Paul has figuratively and literally succumbed to the horror of his apparent existential fate.

Therefore, in terms of the film’s integrity, it is disappointing that Paul is released from his literal prison so shortly thereafter. When Paul falls out the back of the truck and the sculpture he was trapped in shatters, the film betrays the absurd, existential vision it spent so much time building upon. It’s as if what preceded in the previous two hours was shattered–and not in a satisfying way. I suppose one could argue that the film was succumbing to its other significant allusion–The Wizard of Oz [1939]. (Marcy [Rosanna Arquette] speaks about her ex-husband who screamed out “Surrender Dorothy!” with every orgasm, and the film does seem to pattern itself after Dorothy being lost in a strange land and having to find her way back home; I guess there is not much difference between yellow bricks and New York cobblestone.) However, the allusions to Oz are never as significant as are the various direct and indirect existential references and the overall existential tone. Because of this, it doesn’t seem right that it would lean towards a “no place like home” ending albeit one in which Paul is covered in plaster of paris. Supposedly, Martin Scorsese had considered several different endings, one of which had Paul trapped in the sculpture forever. This would have been more in line with the film’s tone.[1]

As it stands, the film’s vision leans more towards the sense that stepping outside the safe yet mundane world of the bourgeoise, corporate-driven culture is an exercise in existential insanity rather than seeing it through the looking glass in which bourgeosie, corporate-driven culture is the slowly-developing existential insanity. The film betrays its own existential underpinnings, its own vision of absurdity. In the end, instead of general existence being absurd and Paul’s everyday life being a delusional bubble, the film’s ending provides the sense that Paul’s everyday life is sane, and the reality of the SoHo artists and bohemians is absurd. Perhaps in the end, this choice was an inadvertent cultural symptom of the New York ’80s art world being compromised and commodified by the corporate world and monied interests at large, or perhaps the choice was not as conscious as that. Perhaps it all came down to an increasingly artificial creative vision that was pervading the film community in the ’80s. Perhaps After Hours more than any other film of the ’80s represents the dichotomy that was occurring at that time; the dichotomy of formulaic fantasy vs. gritty reality. The ’70s golden age of film was clearly over, and even more ironic, Scorsese, one of the cinematic kings of that golden age, had lost his bite.[2] After Hours should have stayed along its original path and maintained its original existential vision. Paul Hackett should have died.

Justin Baker

End Notes

[1] It would have been interesting if Scorsese had taken this one step further and had Paul trapped in the sculpture while being dumped in a landfill. Think of the fascinating social commentary that could have been added to the film’s existential layer in terms of individuals becoming increasingly expendable in our increasingly modern society.

[2] This is particularly ironic when considering the moment that Paul sees an image in a public restroom of a shark biting off a man’s dick—a supposedly sly reference to Jaws [1975] and the blockbuster-film movement killing the ‘70s golden age of cinema, and the fact that Scorsese had migrated to this film only after Paramount had pulled the plug on his first attempt at The Last Temptation of Christ [1988].